Rome (Italian and Latin: Roma [ˈroːma] ⓘ) is the capital city of Italy. It is also the capital of the Lazio region, the centre of the Metropolitan City of Rome Capital, and a special comune named Comune di Roma Capitale. With 2,860,009 residents in 1,285 km2 (496.1 sq mi),[2] Rome is the country’s most populated comune and the third most populous city in the European Union by population within city limits. The Metropolitan City of Rome, with a population of 4,355,725 residents, is the most populous metropolitan city in Italy.[3] Its metropolitan area is the third-most populous within Italy.[4] Rome is located in the central-western portion of the Italian Peninsula, within Lazio (Latium), along the shores of the Tiber. Vatican City (the smallest country in the world)[5] is an independent country inside the city boundaries of Rome, the only existing example of a country within a city. Rome is often referred to as the City of Seven Hills due to its geographic location, and also as the “Eternal City”.[6] Rome is generally considered to be the cradle of Western civilization and Western Christian culture, and the centre of the Catholic Church.[7][8][9]

Rome’s history spans 28 centuries. While Roman mythology dates the founding of Rome at around 753 BC, the site has been inhabited for much longer, making it a major human settlement for almost three millennia and one of the oldest continuously occupied cities in Europe.[10] The city’s early population originated from a mix of Latins, Etruscans, and Sabines. Eventually, the city successively became the capital of the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and is regarded by many as the first-ever Imperial city and metropolis.[11] It was first called The Eternal City (Latin: Urbs Aeterna; Italian: La Città Eterna) by the Roman poet Tibullus in the 1st century BC, and the expression was also taken up by Ovid, Virgil, and Livy.[12][13] Rome is also called “Caput Mundi” (Capital of the World).

After the fall of the Empire in the west, which marked the beginning of the Middle Ages, Rome slowly fell under the political control of the Papacy, and in the 8th century, it became the capital of the Papal States, which lasted until 1870. Beginning with the Renaissance, almost all popes since Nicholas V (1447–1455) pursued a coherent architectural and urban programme over four hundred years, aimed at making the city the artistic and cultural centre of the world.[14] In this way, Rome first became one of the major centres of the Renaissance[15] and then became the birthplace of both the Baroque style and Neoclassicism. Famous artists, painters, sculptors, and architects made Rome the centre of their activity, creating masterpieces throughout the city. In 1871, Rome became the capital of the Kingdom of Italy, which, in 1946, became the Italian Republic.

In 2019, Rome was the 14th most visited city in the world, with 8.6 million tourists, the third most visited city in the European Union, and the most popular tourist destination in Italy.[16] Its historic centre is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.[17] The host city for the 1960 Summer Olympics, Rome is also the seat of several specialised agencies of the United Nations, such as the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Food Programme (WFP) and the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The city also hosts the Secretariat of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Union for the Mediterranean[18] (UfM) as well as the headquarters of many multinational companies, such as Eni, Enel, TIM, Leonardo, and banks such as BNL. Numerous companies are based within Rome’s EUR business district, such as the luxury fashion house Fendi located in the Palazzo della Civiltà Italiana. The presence of renowned international brands in the city has made Rome an important centre of fashion and design, and the Cinecittà Studios have been the set of many Academy Award–winning movies.[19]

Name and symbol

Etymology

According to the Ancient Romans’ founding myth,[20] the name Roma came from the city’s founder and first king, Romulus.[1]

However, it is possible that the name Romulus was actually derived from Rome itself.[21] As early as the 4th century, there have been alternative theories proposed on the origin of the name Roma. Several hypotheses have been advanced focusing on its linguistic roots which however remain uncertain:[22]

- From Rumon or Rumen, archaic name of the Tiber, which in turn is supposedly related to the Greek verb ῥέω (rhéō) ‘to flow, stream’ and the Latin verb ruō ‘to hurry, rush’;[b]

- From the Etruscan word 𐌓𐌖𐌌𐌀 (ruma), whose root is *rum- “teat”, with possible reference either to the totem wolf that adopted and suckled the cognately named twins Romulus and Remus, or to the shape of the Palatine and Aventine Hills;

- From the Greek word ῥώμη (rhṓmē), which means strength.[c]

Other names and symbols

Rome has also been called in ancient times simply “Urbs” (central city),[23] from urbs roma, or identified with its ancient Roman intialism of SPQR, the symbol of Rome’s constituted republican government. Furthermore Rome has been called Urbs Aeterna (The Eternal City), Caput Mundi (The Capital of the world), Throne of St. Peter and Roma Capitale.

History

Main article: History of Rome

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Rome.

Earliest history

Main article: Founding of Rome

Historical States

- Roman Kingdom 753–509 BC

- Roman Republic 509–27 BC

- Roman Empire 27 BC– 395 AD

- Western Roman Empire 286–476

- Kingdom of Italy 476–493

- Ostrogothic Kingdom 493–536

Eastern Roman Empire 536–546

- Ostrogothic Kingdom 546–547

Eastern Roman Empire 547–549

- Ostrogothic Kingdom 549–552

Eastern Roman Empire 552–751

- Kingdom of the Lombards 751–756

Papal States 756–1798

Roman Republic 1798–1799

Papal States 1799–1809

First French Empire 1809–1814

Papal States 1814–1849

Roman Republic 1849

Papal States 1849–1870

Kingdom of Italy 1870–1943

Italian Social Republic 1943–1944

Kingdom of Italy 1944–1946

Italian Republic 1946–present

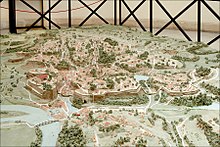

While there have been discoveries of archaeological evidence of human occupation of the Rome area from approximately 14,000 years ago, the dense layer of much younger debris obscures Palaeolithic and Neolithic sites.[10] Evidence of stone tools, pottery, and stone weapons attest to about 10,000 years of human presence. Several excavations support the view that Rome grew from pastoral settlements on the Palatine Hill built above the area of the future Roman Forum. Between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, each hill between the sea and the Capitoline Hill was topped by a village (on the Capitoline, a village is attested since the end of the 14th century BC).[24] However, none of them yet had an urban quality.[24] Nowadays, there is a wide consensus that the city developed gradually through the aggregation (“synoecism“) of several villages around the largest one, placed above the Palatine.[24] This aggregation was facilitated by the increase of agricultural productivity above the subsistence level, which also allowed the establishment of secondary and tertiary activities. These, in turn, boosted the development of trade with the Greek colonies of southern Italy (mainly Ischia and Cumae).[24] These developments, which according to archaeological evidence took place during the mid-eighth century BC, can be considered as the “birth” of the city.[24] Despite recent excavations at the Palatine hill, the view that Rome was founded deliberately in the middle of the eighth century BC, as the legend of Romulus suggests, remains a fringe hypothesis.[25]

Legend of the founding of Rome

Main articles: Romulus and Remus and Romulus

Traditional stories handed down by the ancient Romans themselves explain the earliest history of their city in terms of legend and myth. The most familiar of these myths, and perhaps the most famous of all Roman myths, is the story of Romulus and Remus, the twins who were suckled by a she-wolf.[20] They decided to build a city, but after an argument, Romulus killed his brother and the city took his name. According to the Roman annalists, this happened on 21 April 753 BC.[26] This legend had to be reconciled with a dual tradition, set earlier in time, that had the Trojan refugee Aeneas escape to Italy and found the line of Romans through his son Iulus, the namesake of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.[27] This was accomplished by the Roman poet Virgil in the first century BC. In addition, Strabo mentions an older story, that the city was an Arcadian colony founded by Evander. Strabo also writes that Lucius Coelius Antipater believed that Rome was founded by Greeks.[28][29]

Monarchy and republic

Main articles: Ancient Rome, Roman Kingdom, and Roman Republic

After the foundation by Romulus according to a legend,[26] Rome was ruled for a period of 244 years by a monarchical system, initially with sovereigns of Latin and Sabine origin, later by Etruscan kings. The tradition handed down seven kings: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Lucius Tarquinius Superbus.[26]

In 509 BC, the Romans expelled the last king from their city and established an oligarchic republic. Rome then began a period characterised by internal struggles between patricians (aristocrats) and plebeians (small landowners), and by constant warfare against the populations of central Italy: Etruscans, Latins, Volsci, Aequi, and Marsi.[32] After becoming master of Latium, Rome led several wars (against the Gauls, Osci–Samnites and the Greek colony of Taranto, allied with Pyrrhus, king of Epirus) whose result was the conquest of the Italian peninsula, from the central area up to Magna Graecia.[33]

The third and second century BC saw the establishment of Roman hegemony over the Mediterranean and the Balkans, through the three Punic Wars (264–146 BC) fought against the city of Carthage and the three Macedonian Wars (212–168 BC) against Macedonia.[34] The first Roman provinces were established at this time: Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, Hispania, Macedonia, Achaea and Africa.[35]

From the beginning of the 2nd century BC, power was contested between two groups of aristocrats: the optimates, representing the conservative part of the Senate, and the populares, which relied on the help of the plebs (urban lower class) to gain power. In the same period, the bankruptcy of the small farmers and the establishment of large slave estates caused large-scale migration to the city. The continuous warfare led to the establishment of a professional army, which turned out to be more loyal to its generals than to the republic. Because of this, in the second half of the second century and during the first century BC there were conflicts both abroad and internally: after the failed attempt of social reform of the populares Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus,[36] and the war against Jugurtha,[36] there was a civil war from which the general Sulla emerged victorious.[36] A major slave revolt under Spartacus followed,[37] and then the establishment of the first Triumvirate with Caesar, Pompey and Crassus.[37]

The conquest of Gaul made Caesar immensely powerful and popular, which led to a second civil war against the Senate and Pompey. After his victory, Caesar established himself as dictator for life.[37] His assassination led to a second Triumvirate among Octavian (Caesar’s grandnephew and heir), Mark Antony and Lepidus, and to another civil war between Octavian and Antony.[38]

Empire

Main article: Roman Empire

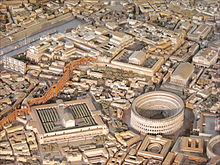

In 27 BC, Octavian became princeps civitatis and took the title of Augustus, founding the principate, a diarchy between the princeps and the senate.[38] During the reign of Nero, two thirds of the city was ruined after the Great Fire of Rome, and the persecution of Christians commenced.[39][40][41] Rome was established as a de facto empire, which reached its greatest expansion in the second century under the Emperor Trajan. Rome was confirmed as caput Mundi, i.e. the capital of the known world, an expression which had already been used in the Republican period. During its first two centuries, the empire was ruled by emperors of the Julio-Claudian,[42] Flavian (who also built an eponymous amphitheatre, known as the Colosseum),[42] and Antonine dynasties.[43] This time was also characterised by the spread of the Christian religion, preached by Jesus Christ in Judea in the first half of the first century (under Tiberius) and popularised by his apostles through the empire and beyond.[44] The Antonine age is considered the zenith of the Empire, whose territory ranged from the Atlantic Ocean to the Euphrates and from Britain to Egypt.[43]

After the end of the Severan Dynasty in 235, the Empire entered into a 50-year period known as the Crisis of the Third Century during which there were numerous putsches by generals, who sought to secure the region of the empire they were entrusted with due to the weakness of central authority in Rome. There was the so-called Gallic Empire from 260 to 274 and the revolts of Zenobia and her father from the mid-260s which sought to fend off Persian incursions. Some regions – Britain, Spain, and North Africa – were hardly affected. Instability caused economic deterioration, and there was a rapid rise in inflation as the government debased the currency in order to meet expenses. The Germanic tribes along the Rhine and north of the Balkans made serious, uncoordinated incursions from the 250s–280s that were more like giant raiding parties rather than attempts to settle. The Persian Empire invaded from the east several times during the 230s to 260s but were eventually defeated.[45] Emperor Diocletian (284) undertook the restoration of the State. He ended the Principate and introduced the Tetrarchy which sought to increase state power. The most marked feature was the unprecedented intervention of the State down to the city level: whereas the State had submitted a tax demand to a city and allowed it to allocate the charges, from his reign the State did this down to the village level. In a vain attempt to control inflation, he imposed price controls which did not last. He or Constantine regionalised the administration of the empire which fundamentally changed the way it was governed by creating regional dioceses (the consensus seems to have shifted from 297 to 313/14 as the date of creation due to the argument of Constantin Zuckerman in 2002 “Sur la liste de Vérone et la province de Grande-Arménie, Mélanges Gilber Dagron). The existence of regional fiscal units from 286 served as the model for this unprecedented innovation. The emperor quickened the process of removing military command from governors. Henceforth, civilian administration and military command would be separate. He gave governors more fiscal duties and placed them in charge of the army logistical support system as an attempt to control it by removing the support system from its control. Diocletian ruled the eastern half, residing in Nicomedia. In 296, he elevated Maximian to Augustus of the western half, where he ruled mostly from Mediolanum when not on the move.[45] In 292, he created two ‘junior’ emperors, the Caesars, one for each Augustus, Constantius for Britain, Gaul, and Spain whose seat of power was in Trier and Galerius in Sirmium in the Balkans. The appointment of a Caesar was not unknown: Diocletian tried to turn into a system of non-dynastic succession. Upon abdication in 305, the Caesars succeeded and they, in turn, appointed two colleagues for themselves.[45]

After the abdication of Diocletian and Maximian in 305 and a series of civil wars between rival claimants to imperial power, during the years 306–313, the Tetrarchy was abandoned. Constantine the Great undertook a major reform of the bureaucracy, not by changing the structure but by rationalising the competencies of the several ministries during the years 325–330, after he defeated Licinius, emperor in the East, at the end of 324. The so-called Edict of Milan of 313, actually a fragment of a letter from Licinius to the governors of the eastern provinces, granted freedom of worship to everyone, including Christians, and ordered the restoration of confiscated church properties upon petition to the newly created vicars of dioceses. He funded the building of several churches and allowed clergy to act as arbitrators in civil suits (a measure that did not outlast him but which was restored in part much later). He transformed the town of Byzantium into his new residence, which, however, was not officially anything more than an imperial residence like Milan or Trier or Nicomedia until given a city prefect in May 359 by Constantius II; Constantinople.[46]

Christianity in the form of the Nicene Creed became the official religion of the empire in 380, via the Edict of Thessalonica issued in the name of three emperors – Gratian, Valentinian II, and Theodosius I – with Theodosius clearly the driving force behind it. He was the last emperor of a unified empire: after his death in 395, his sons, Arcadius and Honorius divided the empire into a western and an eastern part. The seat of government in the Western Roman Empire was transferred to Ravenna in 408, but from 450 the emperors mostly resided in the capital city, Rome.[47]

Rome, which had lost its central role in the administration of the empire, was sacked in 410 by the Visigoths led by Alaric I,[48] but very little physical damage was done, most of which was repaired. What could not be so easily replaced were portable items such as artwork in precious metals and items for domestic use (loot). The popes embellished the city with large basilicas, such as Santa Maria Maggiore (with the collaboration of the emperors). The population of the city had fallen from 800,000 to 450–500,000 by the time the city was sacked in 455 by Genseric, king of the Vandals.[49] The weak emperors of the fifth century could not stop the decay, leading to the deposition of Romulus Augustus on 22 August 476, which marked the end of the Western Roman Empire and, for many historians, the beginning of the Middle Ages.[46]

The decline of the city’s population was caused by the loss of grain shipments from North Africa, from 440 onward, and the unwillingness of the senatorial class to maintain donations to support a population that was too large for the resources available. Even so, strenuous efforts were made to maintain the monumental centre, the palatine, and the largest baths, which continued to function until the Gothic siege of 537. The large baths of Constantine on the Quirinale were even repaired in 443, and the extent of the damage exaggerated and dramatised.[50]

However, the city gave an appearance overall of shabbiness and decay because of the large abandoned areas due to population decline. The population declined to 500,000 by 452 and 100,000 by 500 AD (perhaps larger, though no certain figure can be known). After the Gothic siege of 537, the population dropped to 30,000 but had risen to 90,000 by the papacy of Gregory the Great.[51] The population decline coincided with the general collapse of urban life in the West in the fifth and sixth centuries, with few exceptions. Subsidized state grain distributions to the poorer members of society continued right through the sixth century and probably prevented the population from falling further.[52] The figure of 450,000–500,000 is based on the amount of pork, 3,629,000 lbs. distributed to poorer Romans during five winter months at the rate of five Roman lbs per person per month, enough for 145,000 persons or 1/4 or 1/3 of the total population.[53] Grain distribution to 80,000 ticket holders at the same time suggests 400,000 (Augustus set the number at 200,000 or one-fifth of the population).

Middle Ages

Further information: Fall of the Western Roman Empire

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, Rome was first under the control of Odoacer and then became part of the Ostrogothic Kingdom before returning to East Roman control after the Gothic War, which devastated the city in 546 and 550. Its population declined from more than a million in 210 AD to 500,000 in 273[54] to 35,000 after the Gothic War (535–554),[55] reducing the sprawling city to groups of inhabited buildings interspersed among large areas of ruins, vegetation, vineyards and market gardens.[56] It is generally thought the population of the city until 300 AD was 1 million (estimates range from 2 million to 750,000) declining to 750–800,000 in 400 AD, 450–500,000 in 450 AD and down to 80–100,000 in 500 AD (though it may have been twice this).[57]

The Bishop of Rome, called the Pope, was important since the early days of Christianity because of the martyrdom of both the apostles Peter and Paul there. The Bishops of Rome were also seen (and still are seen by Catholics) as the successors of Peter, who is considered the first Bishop of Rome. The city thus became of increasing importance as the centre of the Catholic Church.

After the Lombard invasion of Italy (569–572), the city remained nominally Byzantine, but in reality, the popes pursued a policy of equilibrium between the Byzantines, the Franks, and the Lombards.[58] In 729, the Lombard king Liutprand donated the north Latium town of Sutri to the Church, starting its temporal power.[58] In 756, Pepin the Short, after having defeated the Lombards, gave the Pope temporal jurisdiction over the Roman Duchy and the Exarchate of Ravenna, thus creating the Papal States.[58] Since this period, three powers tried to rule the city: the pope, the nobility (together with the chiefs of militias, the judges, the Senate and the populace), and the Frankish king, as king of the Lombards, patricius, and Emperor.[58] These three parties (theocratic, republican, and imperial) were a characteristic of Roman life during the entire Middle Ages.[58] On Christmas night of 800, Charlemagne was crowned in Rome as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Leo III: on that occasion, the city hosted for the first time the two powers whose struggle for control was to be a constant of the Middle Ages.[58]

In 846, Muslim Arabs unsuccessfully stormed the city’s walls, but managed to loot St. Peter‘s and St. Paul’s basilica, both outside the city wall.[59] After the decay of Carolingian power, Rome fell prey to feudal chaos: several noble families fought against the pope, the emperor, and each other. These were the times of Theodora and her daughter Marozia, concubines and mothers of several popes, and of Crescentius, a powerful feudal lord, who fought against the Emperors Otto II and Otto III.[60] The scandals of this period forced the papacy to reform itself: the election of the pope was reserved to the cardinals, and reform of the clergy was attempted. The driving force behind this renewal was the monk Ildebrando da Soana, who once elected pope under the name of Gregory VII became involved into the Investiture Controversy against Emperor Henry IV.[60] Subsequently, Rome was sacked and burned by the Normans under Robert Guiscard who had entered the city in support of the Pope, then besieged in Castel Sant’Angelo.[60]

During this period, the city was autonomously ruled by a senatore or patrizio. In the 12th century, this administration, like other European cities, evolved into the commune, a new form of social organisation controlled by the new wealthy classes.[60] Pope Lucius II fought against the Roman commune, and the struggle was continued by his successor Pope Eugenius III: by this stage, the commune, allied with the aristocracy, was supported by Arnaldo da Brescia, a monk who was a religious and social reformer.[61] After the pope’s death, Arnaldo was taken prisoner by Adrianus IV, which marked the end of the commune’s autonomy.[61] Under Pope Innocent III, whose reign marked the apogee of the papacy, the commune liquidated the senate, and replaced it with a Senatore, who was subject to the pope.[61]

In this period, the papacy played a role of secular importance in Western Europe, often acting as arbitrators between Christian monarchs and exercising additional political powers.[62][63][64]

In 1266, Charles of Anjou, who was heading south to fight the Hohenstaufen on behalf of the pope, was appointed Senator. Charles founded the Sapienza, the university of Rome.[61] In that period the pope died, and the cardinals, summoned in Viterbo, could not agree on his successor. This angered the people of the city, who then unroofed the building where they met and imprisoned them until they had nominated the new pope; this marked the birth of the conclave.[61] In this period the city was also shattered by continuous fights between the aristocratic families: Annibaldi, Caetani, Colonna, Orsini, Conti, nested in their fortresses built above ancient Roman edifices, fought each other to control the papacy.[61]

Pope Boniface VIII, born Caetani, was the last pope to fight for the church’s universal domain; he proclaimed a crusade against the Colonna family and, in 1300, called for the first Jubilee of Christianity, which brought millions of pilgrims to Rome.[61] However, his hopes were crushed by the French king Philip the Fair, who took him prisoner and killed him in Anagni.[61] Afterwards, a new pope faithful to the French was elected, and the papacy was briefly relocated to Avignon (1309–1377).[65] During this period Rome was neglected, until a plebeian man, Cola di Rienzo, came to power.[65] An idealist and a lover of ancient Rome, Cola dreamed about a rebirth of the Roman Empire: after assuming power with the title of Tribuno, his reforms were rejected by the populace.[65] Forced to flee, Cola returned as part of the entourage of Cardinal Albornoz, who was charged with restoring the Church’s power in Italy.[65] Back in power for a short time, Cola was soon lynched by the populace, and Albornoz took possession of the city. In 1377, Rome became the seat of the papacy again under Gregory XI.[65] The return of the pope to Rome in that year unleashed the Western Schism (1377–1418), and for the next forty years, the city was affected by the divisions which rocked the Church.[65]

Early modern history

Main article: Roman Renaissance

In 1418, the Council of Constance settled the Western Schism, and a Roman pope, Martin V, was elected.[65] This brought to Rome a century of internal peace, which marked the beginning of the Renaissance.[65] The ruling popes until the first half of the 16th century, from Nicholas V, founder of the Vatican Library, to Pius II, humanist and literate, from Sixtus IV, a warrior pope, to Alexander VI, immoral and nepotist, from Julius II, soldier and patron, to Leo X, who gave his name to this period (“the century of Leo X”), all devoted their energy to the greatness and the beauty of the Eternal City and to the patronage of the arts.[65]

During those years, the centre of the Italian Renaissance moved to Rome from Florence. Majestic works, as the new Saint Peter’s Basilica, the Sistine Chapel and Ponte Sisto (the first bridge to be built across the Tiber since antiquity, although on Roman foundations) were created. To accomplish that, the Popes engaged the best artists of the time, including Michelangelo, Perugino, Raphael, Ghirlandaio, Luca Signorelli, Botticelli, and Cosimo Rosselli.

The period was also infamous for papal corruption, with many Popes fathering children, and engaging in nepotism and simony. The corruption of the Popes and the huge expenses for their building projects led, in part, to the Reformation and, in turn, the Counter-Reformation. Under extravagant and rich popes, Rome was transformed into a centre of art, poetry, music, literature, education and culture. Rome became able to compete with other major European cities of the time in terms of wealth, grandeur, the arts, learning and architecture.

The Renaissance period changed the face of Rome dramatically, with works like the Pietà by Michelangelo and the frescoes of the Borgia Apartments. Rome reached the highest point of splendour under Pope Julius II (1503–1513) and his successors Leo X and Clement VII, both members of the Medici family.

In this twenty-year period, Rome became one of the greatest centres of art in the world. The old St. Peter’s Basilica built by Emperor Constantine the Great[66] (which by then was in a dilapidated state) was demolished and a new one begun. The city hosted artists like Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Botticelli and Bramante, who built the temple of San Pietro in Montorio and planned a great project to renovate the Vatican. Raphael, who in Rome became one of the most famous painters of Italy, created frescoes in the Villa Farnesina, the Raphael’s Rooms, plus many other famous paintings. Michelangelo started the decoration of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and executed the famous statue of the Moses for the tomb of Julius II.

Its economy was rich, with the presence of several Tuscan bankers, including Agostino Chigi, who was a friend of Raphael and a patron of arts. Before his early death, Raphael also promoted for the first time the preservation of the ancient ruins. The War of the League of Cognac caused the first plunder of the city in more than five hundred years since the previous sack; in 1527, the Landsknechts of Emperor Charles V sacked the city, bringing an abrupt end to the golden age of the Renaissance in Rome.[65]

Beginning with the Council of Trent in 1545, the Church began the Counter-Reformation in response to the Reformation, a large-scale questioning of the Church’s authority on spiritual matters and governmental affairs. This loss of confidence led to major shifts of power away from the Church.[65] Under the popes from Pius IV to Sixtus V, Rome became the centre of a reformed Catholicism and saw the building of new monuments which celebrated the papacy.[67] The popes and cardinals of the 17th and early 18th centuries continued the movement by having the city’s landscape enriched with baroque buildings.[67]

This was another nepotistic age; the new aristocratic families (Barberini, Pamphili, Chigi, Rospigliosi, Altieri, Odescalchi) were protected by their respective popes, who built huge baroque buildings for their relatives.[67] During the Age of Enlightenment, new ideas reached the Eternal City, where the papacy supported archaeological studies and improved the people’s welfare.[65] But not everything went well for the Church during the Counter-Reformation. There were setbacks in the attempts to assert the Church’s power, a notable example being in 1773 when Pope Clement XIV was forced by secular powers to have the Jesuit order suppressed.[65]

Late modern and contemporary

The rule of the Popes was interrupted by the short-lived Roman Republic (1798–1800), which was established under the influence of the French Revolution. The Papal States were restored in June 1800, but during Napoleon‘s reign Rome was annexed as a Département of the French Empire: first as Département du Tibre (1808–1810) and then as Département Rome (1810–1814). After the fall of Napoleon, the Papal States were reconstituted by a decision of the Congress of Vienna of 1814.

In 1849, a second Roman Republic was proclaimed during a year of revolutions in 1848. Two of the most influential figures of the Italian unification, Giuseppe Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi, fought for the short-lived republic.

Rome then became the focus of hopes of Italian reunification after the rest of Italy was united as the Kingdom of Italy in 1861 with the temporary capital in Florence. That year Rome was declared the capital of Italy even though it was still under the Pope’s control. During the 1860s, the last vestiges of the Papal States were under French protection thanks to the foreign policy of Napoleon III. French troops were stationed in the region under Papal control. In 1870 the French troops were withdrawn due to the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. Italian troops were able to capture Rome entering the city through a breach near Porta Pia. Pope Pius IX declared himself a prisoner in the Vatican. In 1871 the capital of Italy was moved from Florence to Rome.[68] In 1870 the population of the city was 212,000, all of whom lived with the area circumscribed by the ancient city, and in 1920, the population was 660,000. A significant portion lived outside the walls in the north and across the Tiber in the Vatican area.

Soon after World War I in late 1922 Rome witnessed the rise of Italian Fascism led by Benito Mussolini, who led a march on the city. He did away with democracy by 1926, eventually declaring a new Italian Empire and allying Italy with Nazi Germany in 1938. Mussolini demolished fairly large parts of the city centre in order to build wide avenues and squares which were supposed to celebrate the fascist regime and the resurgence and glorification of classical Rome.[69] The interwar period saw a rapid growth in the city’s population which surpassed one million inhabitants soon after 1930. During World War II, due to the art treasuries and the presence of the Vatican, Rome largely escaped the tragic destiny of other European cities. However, on 19 July 1943, the San Lorenzo district was subject to Allied bombing raids, resulting in about 3,000 fatalities and 11,000 injuries, of whom another 1,500 died.[70] Mussolini was arrested on 25 July 1943. On the date of the Italian Armistice 8 September 1943 the city was occupied by the Germans. The Pope declared Rome an open city. It was liberated on 4 June 1944.

Rome developed greatly after the war as part of the “Italian economic miracle” of post-war reconstruction and modernisation in the 1950s and early 1960s. During this period, the years of la dolce vita (“the sweet life”), Rome became a fashionable city, with popular classic films such as Ben Hur, Quo Vadis, Roman Holiday and La Dolce Vita filmed in the city’s iconic Cinecittà Studios. The rising trend in population growth continued until the mid-1980s when the comune had more than 2.8 million residents. After this, the population declined slowly as people began to move to nearby suburbs.

information from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bars

Pubs

Bad and Breakfast

Hostel

Hotel